Ever since 1669, when Huang Zongxi first described Chinese martial arts in terms of a Shaolin or "external" school versus a Wudang or "internal" school,[1] "Shaolin" has been used as a synonym for "external" Chinese martial arts regardless of whether or not the particular style in question has any connection to the Shaolin Monastery. In 1784 the Boxing Classic: Essential Boxing Methods[2] made the earliest extant reference to the Shaolin Monastery as Chinese boxing's place of origin.[3]

Since the beginning of the 17th century, the Shaolin Monastery garnered such fame that many martial artists have capitalized on its name by claiming possession of the original, authentic Shaolin teachings.[4]

The oldest evidence of Shaolin participation in combat is a stele from 728 that attests to two occasions: a defense of the monastery from bandits around 610 and their role in the defeat of Wang Shichong at the Battle of Hulao in 621.

Like most dynastic changes, the end of the Sui Dynasty was a time of upheaval and contention for the throne. Wang Shichong declared himself Emperor. He controlled the territory of Zheng and the ancient capital of Luoyang.

Overlooking Luoyang on Mount Huanyuan was the Cypress Valley Estate, which had served as the site of a fort during the Jin and a commandery during the Southern Qi.[5] Sui Emperor Wen had bestowed the estate on a nearby monastery called Shaolin for its monks to farm but Wang Shichong, realizing its strategic value, seized the estate and there placed troops and a signal tower, as well as establishing a prefecture called Yuanzhou.[5] Furthermore, he had assembled an army at Luoyang to march on the Shaolin Temple itself.

The monks of Shaolin allied with Wang's enemy, Li Shimin, and took back the Cypress Valley Estate, defeating Wang's troops and capturing his nephew Renze.

Without the fort at Cypress Valley, there was nothing to keep Li Shimin from marching on Luoyang after his defeat of Wang's ally Dou Jiande at the Battle of Hulao, forcing Wang Shichong to surrender.

Li Shimin's father was the first Tang Emperor and Shimin himself became its second.

Thereafter Shaolin enjoyed the royal patronage of the Tang.

Though the Shaolin Monastery Stele of 728 attests to these incidents in 610 and 621 when the monks engaged in combat, note that it does not allude to martial training in the monastery, or to any fighting technique in which its monks specialized. Nor do any other sources from the Tang, Song and Yuan periods allude to military training at the temple, so even if it is possible or even likely that the Shaolin monastic regimen included martial arts, there is no documentation of it. According to Meir Shahar, this is explained by a confluence of the late-Ming fashion for military encyclopedias and, more importantly, the conscription of civilian irregulars—including monks—as a result of Ming military decline in the 16th century.[4]

From the 8th to the 15th centuries, no extant source documents Shaolin participation in combat; then suddenly, the 16th and 17th centuries see at least forty extant sources attest that, not only did monks of Shaolin practice martial arts, but martial practice had become such an integral element of Shaolin monastic life that the monks felt the need to justify it by creating new Buddhist lore.[4]References to Shaolin martial arts appear in various literary genres of the late Ming: the epitaphs of Shaolin warrior monks, martial-arts manuals, military encyclopedias, historical writings, travelogues, fiction, and even poetry.[4]

These sources, in contrast to those from the Tang Dynasty period, refer to Shaolin methods of combat unarmed, with the spear, and with the weapon that was the forte of the Shaolin monks and for which they had become famous—the staff.[4][3] By the mid-16th century military experts from all over Ming China were travelling to Shaolin to study its fighting techniques.

Around 1560 Yú Dàyóu travelled to Shaolin Monastery to see for himself its monks' fighting techniques, but found them disappointing. Yú returned to the south with two monks, Zongqing and Pucong, whom he taught the use of the staff over the next three years, after which Zongqing and Pucong returned to Shaolin Monastery and taught their brother monks what they had learned. Martial arts historian Tang Hao traced the Shaolin staff style Five Tigers Interception to Yú's teachings.

The earliest extant manual on Shaolin Kung Fu, the Exposition of the Original Shaolin Staff Method[6] was written around 1610 and published in 1621 from what its author Chéng Zōngyóu learned during a more than ten year stay at the monastery.

Conditions of lawlessness in Henan—where the Shaolin Monastery is located—and surrounding provinces during the late Ming Dynasty and all of the Qing Dynasty contributed to the development of martial arts. Meir Shahar lists the martial arts T'ai Chi Ch'üan, Chang Family Boxing, Bāguàquán, Xíngyìquán and Bājíquán as originating from this region and this time period.[4]

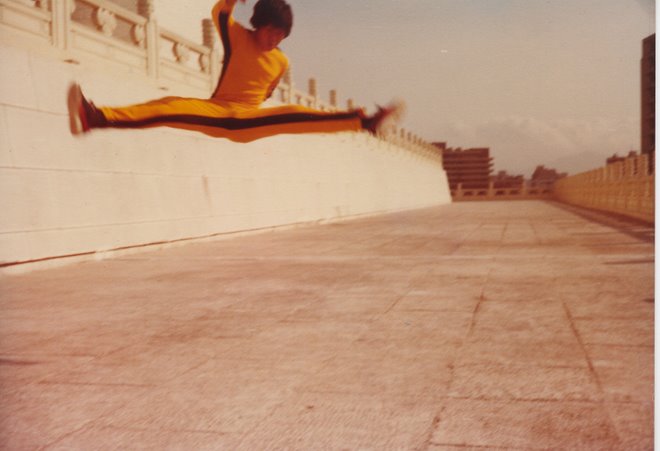

All Martial Arts of this world were created under the sun of Shaolin. Shaolin Kung Fu is as vast and complex as the universe. This site will barely scratch the surface of its depths. An ancient Shaolin Master once said: "Study Shaolin Style in great depth, then absorb the special qualities of other styles. Set for your high ideals. Study for wisdom and train the body. Never fear evil. Always fight for Justice." A good soldier is not violent. A good fighter is not furious. A good winner is not vindictive.

Since the beginning of the 17th century, the Shaolin Monastery garnered such fame that many martial artists have capitalized on its name by claiming possession of the original, authentic Shaolin teachings.[4]

The oldest evidence of Shaolin participation in combat is a stele from 728 that attests to two occasions: a defense of the monastery from bandits around 610 and their role in the defeat of Wang Shichong at the Battle of Hulao in 621.

Like most dynastic changes, the end of the Sui Dynasty was a time of upheaval and contention for the throne. Wang Shichong declared himself Emperor. He controlled the territory of Zheng and the ancient capital of Luoyang.

Overlooking Luoyang on Mount Huanyuan was the Cypress Valley Estate, which had served as the site of a fort during the Jin and a commandery during the Southern Qi.[5] Sui Emperor Wen had bestowed the estate on a nearby monastery called Shaolin for its monks to farm but Wang Shichong, realizing its strategic value, seized the estate and there placed troops and a signal tower, as well as establishing a prefecture called Yuanzhou.[5] Furthermore, he had assembled an army at Luoyang to march on the Shaolin Temple itself.

The monks of Shaolin allied with Wang's enemy, Li Shimin, and took back the Cypress Valley Estate, defeating Wang's troops and capturing his nephew Renze.

Without the fort at Cypress Valley, there was nothing to keep Li Shimin from marching on Luoyang after his defeat of Wang's ally Dou Jiande at the Battle of Hulao, forcing Wang Shichong to surrender.

Li Shimin's father was the first Tang Emperor and Shimin himself became its second.

Thereafter Shaolin enjoyed the royal patronage of the Tang.

Though the Shaolin Monastery Stele of 728 attests to these incidents in 610 and 621 when the monks engaged in combat, note that it does not allude to martial training in the monastery, or to any fighting technique in which its monks specialized. Nor do any other sources from the Tang, Song and Yuan periods allude to military training at the temple, so even if it is possible or even likely that the Shaolin monastic regimen included martial arts, there is no documentation of it. According to Meir Shahar, this is explained by a confluence of the late-Ming fashion for military encyclopedias and, more importantly, the conscription of civilian irregulars—including monks—as a result of Ming military decline in the 16th century.[4]

From the 8th to the 15th centuries, no extant source documents Shaolin participation in combat; then suddenly, the 16th and 17th centuries see at least forty extant sources attest that, not only did monks of Shaolin practice martial arts, but martial practice had become such an integral element of Shaolin monastic life that the monks felt the need to justify it by creating new Buddhist lore.[4]References to Shaolin martial arts appear in various literary genres of the late Ming: the epitaphs of Shaolin warrior monks, martial-arts manuals, military encyclopedias, historical writings, travelogues, fiction, and even poetry.[4]

These sources, in contrast to those from the Tang Dynasty period, refer to Shaolin methods of combat unarmed, with the spear, and with the weapon that was the forte of the Shaolin monks and for which they had become famous—the staff.[4][3] By the mid-16th century military experts from all over Ming China were travelling to Shaolin to study its fighting techniques.

Around 1560 Yú Dàyóu travelled to Shaolin Monastery to see for himself its monks' fighting techniques, but found them disappointing. Yú returned to the south with two monks, Zongqing and Pucong, whom he taught the use of the staff over the next three years, after which Zongqing and Pucong returned to Shaolin Monastery and taught their brother monks what they had learned. Martial arts historian Tang Hao traced the Shaolin staff style Five Tigers Interception to Yú's teachings.

The earliest extant manual on Shaolin Kung Fu, the Exposition of the Original Shaolin Staff Method[6] was written around 1610 and published in 1621 from what its author Chéng Zōngyóu learned during a more than ten year stay at the monastery.

Conditions of lawlessness in Henan—where the Shaolin Monastery is located—and surrounding provinces during the late Ming Dynasty and all of the Qing Dynasty contributed to the development of martial arts. Meir Shahar lists the martial arts T'ai Chi Ch'üan, Chang Family Boxing, Bāguàquán, Xíngyìquán and Bājíquán as originating from this region and this time period.[4]

All Martial Arts of this world were created under the sun of Shaolin. Shaolin Kung Fu is as vast and complex as the universe. This site will barely scratch the surface of its depths. An ancient Shaolin Master once said: "Study Shaolin Style in great depth, then absorb the special qualities of other styles. Set for your high ideals. Study for wisdom and train the body. Never fear evil. Always fight for Justice." A good soldier is not violent. A good fighter is not furious. A good winner is not vindictive.

No comments:

Post a Comment